Today, we present a guest post written by David Papell and Ruxandra Prodan, Professor and Instructional Associate Professor of Economics at the University of Houston.

The Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) raised the target range for the federal funds rate (FFR) by 50 basis points from 0.25 – 0.5 percent to 0.75 – 1.0 percent at its May 4 meeting and “anticipates that ongoing increases in the target range will be appropriate.” This followed a 25 basis point increase from the effective lower bound (ELB) of 0.0 – 0.25 percent in the March meeting, the first increase from the ELB in two years. In the press conference following the meeting, Fed Chair Powell went further by saying that “There is a broad sense on the committee that additional 50 basis point increases should be on the table for the next couple of meetings.”

The FOMC has been the subject of criticism for falling “behind the curve” by failing to raise the FFR in the face of rising inflation. In a recent paper, “Policy Rules and Forward Guidance Following the Covid-19 Recession,” we show how the FFR fell behind policy rule prescriptions and what it would take to get back “on track”.

Much of the discussion of the Fed being behind the curve depends on subjective analysis of when liftoff from the ELB should have occurred. We use data from the Summary of Economic Projections (SEP) from September 2020 to March 2022 to compare policy rule prescriptions with actual and FOMC projections of the FFR. This provides a precise definition of “behind the curve” as the difference between the FFR prescribed by policy rules and the actual FFR.

The FOMC adopted a far-reaching Revised Statement on Longer-Run Goals and Monetary Policy Strategy in August 2020. The framework contains two major changes from the original 2012 statement. First, policy decisions will attempt to mitigate shortfalls, rather than deviations, of employment from its maximum level. Second, the FOMC will implement Flexible Average Inflation Targeting where, “following periods when inflation has been running persistently below 2 percent, appropriate monetary policy will likely aim to achieve inflation moderately above 2 percent for some time.”

At its September 2020 meeting, the Committee approved outcome-based forward guidance, saying that it expected to maintain the target range of the FFR at the ELB “until labor market conditions have reached levels consistent with the Committee’s assessment of maximum employment and inflation has risen to 2 percent and is on track to moderately exceed 2 percent for some time.”

We consider six policy rules. The Taylor (1993) rule prescribes that the FFR equal the inflation rate plus 0.5 times the inflation gap, the difference between the inflation rate and the 2 percent inflation target, plus 1.0 times the unemployment gap, the difference between the rate of unemployment in the longer run and the realized unemployment rate, plus the neutral real interest rate. The balanced approach rule in Yellen (2012) raises the coefficient on the unemployment gap to 2.0 while maintaining the coefficient of 0.5 on the inflation gap. The Taylor and balanced approach (shortfalls) rules are identical to the original rules except that they do not prescribe a rise in the FFR when unemployment falls below longer-run unemployment.

Neither the original nor the shortfalls rules are consistent with the revised statement. We introduce two new rules in accord with the revised statement that we call the Taylor and balanced approach (consistent) rules. First, we replace the rate of unemployment in the longer run with the unemployment rate consistent with maximum employment and base FFR prescriptions on shortfalls instead of deviations. Second, if inflation rises above 2 percent, the rule is amended to allow it to equal the inflation rate “moderately” above 2 percent that the FOMC is willing to tolerate “for some time” before raising rates in order to bring inflation down to the 2 percent target.

Starting with the original Taylor rule, normative policy rule prescriptions are typically “non-inertial” as the prescribed FFR depends on the realized values of the right-hand-side variables. Following Clarida, Gali, and Gertler (1999), estimated Taylor-type rules are typically “inertial” to incorporate slow adjustment of the actual FFR to changes in the prescribed FFR. Policy rule forward guidance, however, involves normative policy rule prescriptions that need to be inertial when inflation rises quickly in order to be in accord with the FOMC’s desire to smooth out large rate increases over time. We follow Bernanke, Kiley, and Roberts (2019) and specify inertial rules with a coefficient of 0.85 on the lagged FFR and 0.15 on the target level of the FFR specified by the corresponding non-inertial rule.

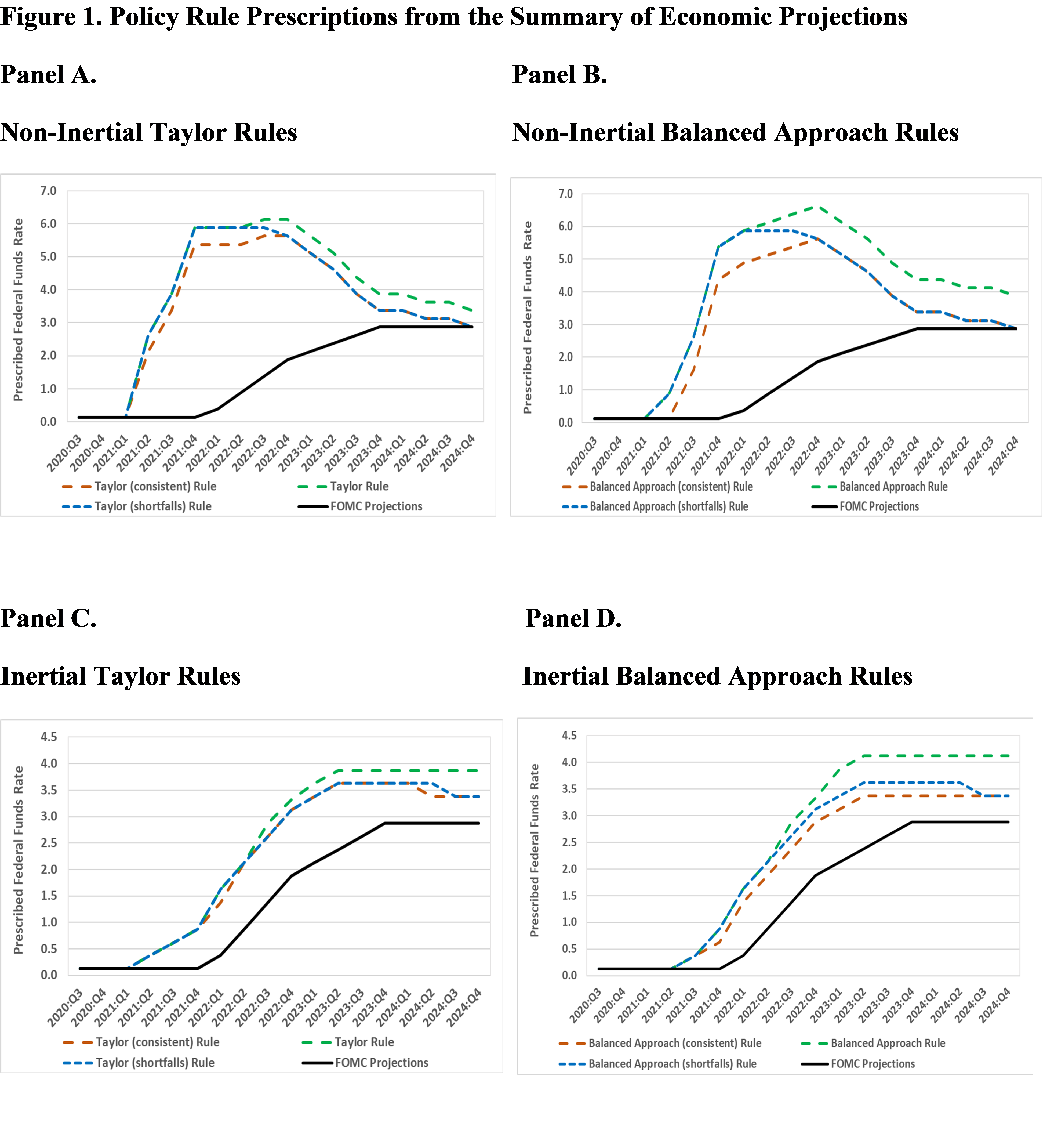

Figure 1 depicts the actual FFR for September 2020 to March 2022 and the projected FFR from the March 2022 SEP for June 2022 to December 2024. Following liftoff from the ELB in March 2022, the FOMC projected six more 25 basis point rate increases (one each meeting) in 2022, four 25 basis point rate increases (one every other meeting) in 2023, and a constant range of the FFR of 2.75 – 3.0 percent in 2024. The FOMC has already exceeded that pace by increasing the FFR by 50 basis points on May 4.

Panels A and B illustrate prescriptions from the non-inertial rules. Five of the six rules prescribe liftoff from the ELB in 2021:Q2, three quarters earlier than the actual liftoff. All of the non-inertial rules prescribe unrealistic jumps in the FFR. For the Taylor rules, there are prescribed jumps of at least 200 basis points in 2021:Q2 and 2021:Q4 and, for the balanced approach rules, there is a 275 basis point jump in 2021:Q4. The prescribed rate increases peak by the end of 2022 and, for the shortfalls and consistent rules, which are more in accord with Fed policy than the original rules, the prescriptions are equal to the FOMC projections at the end of 2024.

Panels C and D show prescriptions from the inertial rules. The prescribed liftoff from the ELB is slightly later than with the non-inertial rules, 2021:Q2 for the Taylor rules and 2021:Q3 for the balanced approach rules. The inertial rules prescribe much more realistic paths for the FFR than the non-inertial rules. Almost all of the prescribed rate increases are 25 basis points and there are no increases greater than 50 basis points. In March 2022, the prescribed FFR’s were 1.25 percent higher than the actual FFF for the original and shortfalls rules and 1.0 percent higher for the consistent rules. The prescribed FFR’s with the inertial rules continue to increase but much more slowly than those with the non-inertial rules. At the end of 2024, the prescribed FFR’s with the shortfalls and consistent rules are 50 basis points higher than the FOMC projections.

Following the 50 basis point increase in the FFR at its May 4 meeting, how can the FOMC eliminate the gap between the inertial policy rule prescriptions and the FFR in its five remaining meetings by the end of 2022? For the Taylor rules, it would take five 1/2 percent rate increases to close the gap for the original rule and four 1/2 percent rate increases and one 1/4 percent rate increase to close the gap for the shortfalls and the consistent rules. For the balanced approach rules, it would take five 1/2 percent rate increases to close the gap for the original rule, four 1/2 percent rate increases and one 1/4 percent rate increase to close the gap for the shortfalls rule, and four 1/2 percent rate increases to close the gap for the consistent rule.

The Fed fell behind the curve by not following prescriptions from policy rules that are consistent with its own goals and strategies. Raising the FFR by 50 basis points on May 4 and signaling more increases was a good first step, but it will take at least four more 50 basis point increases to get back on track.

This post written by David Papell and Ruxandra Prodan.